| Meta's grandfather, Jacob J. Goering, had died in 1911, three years before Jonas was

married. In 1914 Jonas and Katie moved into the Goering home place. Jonas' mother, Anna,

for a time stayed with her other sons, but eventually returned to live with Jonas and

Katie--for the next thirty-six years. The farm was located in Mound township, a mile and

half north and a half mile east of the Hoffnunsfeld-Eden church which was the center of

the Mennonite settlement. Three of Jonas's brothers--Christian, Henry, and Jacob--also

started farm families nearby. The Goering brothers had farm equipment in common--wheat

threshing rig, manure spreader, and others. They also shared farm labor, Sunday visits,

and larger family celebrations. It was a somewhat more closely knit extended family than

that of Ernest Juhnke and his siblings. The Jonas Goering farmstead hosted more of the

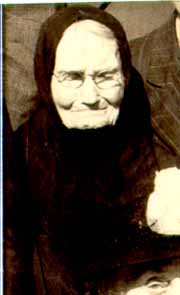

celebrations because that was where Grandma Anna lived. Every year on Grandma's birthday,

January 28, all her children and grandchildren arrived to celebrate. The menu was the same

every time--bologna, cheese, crackers, and ice cream from town. Aunt Freni was acclaimed

for her angel food cake. But Jonas and Katie also made a point of staying in touch with

their other brothers and sisters as well, which in most cases meant Sunday visits at least

once a year. Meta especially enjoyed going to Uncle Chris and Aunt Adina's place, because

their daughter Anna was just Meta's age. "I always had companions wherever I

went," remembered Meta. On one occasion when Meta was still quite small, she was

visiting at her Uncle Jake and Aunt Lydia's place a half mile to the west when a visiting

farmer was badly hurt in an machinery accident. Meta watched wide-eyed as people scurried

about until the doctor came and applied the anaesthetic and treatment. At one point the

worried little Meta said, "If only the Good Samaritan would come by now!" She

had learned in Sunday School that the Good Samaritan knew how to help people who were in

trouble.

Meta's grandparents were Swiss-background Mennonites who emigrated from Polish Russia

(Volhynia) to Kansas in 1874. The immigrant consciousness of the community was strong.

When Meta was a senior at Moundridge High School, she wrote a short autobiography

("Copyright 1931. All rights reserved.") . Her first chapter was "How My

Forefathers Came to America." The migration was triggered, Meta reported, by loss of

religious freedom. The Mennonites opposed military service and decided to go to America

rather than compromise their religious beliefs. In Kansas they "worked hard and saved

money so that they were soon comfortably well-to-do and respected people." |