|

Bill and Meta Juhnke lived their lives in a century of total war. They were born (1912 and 1916) shortly before the United States entered World War I. They were a young married couple when the world, hardly made "safe for democracy" by one great war, drifted into an even more devastating World War II (1938-45). And they died (1991 and 1996) at the end of a Cold War era that armed the nations with thousands of nuclear weapons that could destroy human civilization several times over. Although Bill was not caught in the military draft, warfare and its consequences affected him and his family at every stage of life. In the 1930s and 1940s he underwent a passage, typical of American peace advocates generally, from optimistic liberal hope for world peace to discouragement in the face of a world gone mad with war. For Bill it was part of a sobering transition from youth to middle age. In their childhood years, Bill and Meta learned the Christian gospel of peace at the Eden Mennonite Church. In college, Bill's favorite teachers were strong spokesmen for peace in the "historic peace church" tradition: Maurice Hess at McPherson College, and Emmet Harshbarger and Ed. G. Kaufman at Bethel College. These men believed that the Christian peace witness applied to personal relations as well as international relations. In his history classes, Harshbarger assigned readings from "revisionist" historians Charles Beard and Harry Elmer Barnes. The "revisionists" argued that Germany was not solely responsible for the outbreak of World War I, that the punitive Versailles Treaty was a mistake, and that the United States had been drawn into the war by misleading propaganda and by the machinations of profit-seeking corporations. At Bethel College Bill was taught what he called "the position of Christian peace," a position shaped not only by Mennonite interpretations of the Bible and theology, but also by "revisionist" understandings of recent history and international relations. Bill graduated from Bethel College in May 1936. The next month, Bethel College hosted the first of five yearly summer adult education Peace Institutes, sponsored the American Friends Service Committee. Officially called the "Institute of International Relations," these were adult education courses lasting a week to ten days, and attended by peace-movement people from a variety of backgrounds. An Institute report for 1938 claimed that people had attended from forty-eight towns and seventeen different denominations, although the full-day tuition-paying number was much smaller. The institute teachers were prominent peace-minded ministers and scholars, such as Dr. Frederick W. Norwood, Minister of the City Temple in London; Rev. Charles M. Sheldon, author of the best seller, In His Steps; Dr. Sidney B. Fay, revisionist historian from Harvard University; and Clarence Streit, prominent advocate of a North Atlantic political union. The high point of Institute public exposure was in 1939 when Dr. Eduard Benes, an international celebrity who had been ousted as president of Czechoslovakia for opposing Nazi expansion, was a speaker. The Institute sessions were scheduled in June, a busy time for farmers, so Bill did not attend the day sessions as a tuition-paying participant. But he did attend some of the evening public events. In February 1939 Donovan Smucker, Institute director for that year, invited Bill to serve on the Peace Institute steering committee. Bill was able to use his positions as president of the Western District Christian Endeavor and editor of Western District Tidings to support Peace Institute events. In May 1939 he sent to congregational WDCE officers an enthusiastic promotional statement, "Why Mennonite C. E. Societies Should Support the Kansas Institute of International Relations." He wrote that the Institute "gives the Mennonites the very best way to carry their message directly to non-Mennonites–those that are church, community and educational leaders who would not otherwise come into contact with this Mennonite principle." Here was an opportunity for Mennonites, often accused of "doing nothing except refusing to participate in war, . . . to do something constructive for peace and goodwill." Bill encouraged Christian Endeavor societies to support the Institute financially and to attend the annual meetings, to learn "information as to the causes of wars, ways to peaceful settlement of international disputes, and methods of propaganda." In the 1930s peace advocates made their witness at the center, not at the margins, of public life. Political leaders in Kansas, at both state and local levels, were remarkably peace-minded in the 1930s, even as aggressor states in Europe and Asia made their drives for expansion. (Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931; Hitler rearmed Germany after Nazis came to power in 1933; Italy took Ethiopia in 1935.) Arthur Capper, Republican senator of Quaker background, promoted non-interventionist policies until Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, December 1941. John M. Houston, Democrat congressman from Newton (1934-42) spoke out strongly against "sending American soldiers to foreign battlefields." In Moundridge, Kansas, where Bill Juhnke started teaching in 1936, the editor of the Moundridge Journal, Vernard Vogt, maintained an anti-war editorial stance until the spring of 1941. Vogt was of German Evangelical background, a member of the Methodist Church in Moundridge. On September 2, 1937, he warned readers not to believe that "Same Old Bunk" propagandistic atrocity stories coming out of Europe. On January 13, 1938, the editor recalled the official lies about the sinking of the Maine (1898) and the Lusitania (1915) that misled the United States into the Spanish American War and World War I. "Every sane man abhors war," he wrote. "Every good American abhors it." Even after Germany had invaded Poland, and England and France had declared war on Germany, Vogt wrote that, despite sympathies for the allies, "we are not going to do any killing if we can help it." On November 14, 1940, Vogt wrote an Armistice Day editorial critical of how the winners of World War I had botched their opportunity. "The conqueror stresses his victory by acting first and thinking afterwards. The sore festers, healing only on the surface. . . . Too late we learn that the ‘cease firing' of 1918 was only prolonged to pass to another generation." But by Memorial Day, May 29, 1941, Vogt had flip-flopped to patriotic militarism: "Wars are blights on the pages of history, yet history points out that the daring ‘have not died in vain' for there comes from the smoke of battlefield a cleansing of purpose and a new spirit that strives to bring about peace with honor, peace with justice, and armistice for the world." On December 18, 1941, he wrote, "One of the strangest things about our search for peace is the fact that the path to it is often a warpath." |

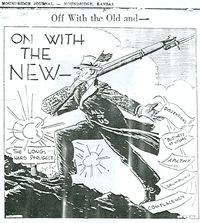

Editorial cartoon, "On With The

New,"

Moundridge Journal, January 28, 1942

|

In his first five years of teaching at Moundridge High School (1936-1941), Bill could press peace issues in his classes and extracurricular activities without necessarily offending prevailing public opinion. It was a strongly anti-war community, with a substantial Mennonite presence. On November 11, 1936, Bill's constitution class led the student assembly in a celebration of Armistice Day. He urged his students to keep abreast of current events, and had them give reports and assemble newspaper clippings on national issues such as "Lend-Lease" legislation for the U.S. to provide aid to the allies. On October 13, 1939, Bill wrote to Kansas Senator Clyde M. Reed, using Moundridge Public School letterhead and signing as "Head of the Social Science Department." He expressed concern over Reed's apparent willingness to approve some credit to war belligerents. As sponsor of the high school young men's Christian organization, the Hi-Y, Bill helped organize peace programs. At a Hi-Y program of March 16, 1940, "Marvin Stucky reminded us of the Christian's attitude on war, speaking on the topic, ‘Will a Christian Fight?'" and Arnold Goertz spoke on the prospect of American intervention with the title, "Keep America Out of War." The national Hi-Y organization took a strong non-interventionist position. Youth delegates at their summer 1940 convention pledged that they would "refuse to fight in Europe, but only help defend the western hemisphere." No issue was of greater personal interest to Bill than the prospect of military conscription. In July, 1940, he began his own extensive file of newspaper clippings about draft-related questions. He pasted the clippings from the Wichita newspapers, and other unidentified newspapers, onto 8½ by 11 inch sheets. When the U.S. Senate voted in favor of peacetime conscription, August 28, 1940, Kansas senators Capper and Reed voted against the measure. The stated penalty for violating the Selective Service Act was five years in prison. The first draft registration, October 16, 1940, was for men ages 21-35. Bill Juhnke was 28 years old. A draft lottery followed on October 29, to randomly draw numbers that would determine in what order the young men would be called to camp for military training. Draft officials estimated that the first twenty-five numbers would cover the first call for the training camps. Bill's registration number (#2148) was drawn way down the line–8686. He was classified III-A, a "dependency deferment" granted to fathers with children under age eighteen. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the American declaration of war (December 7-8, 1941), peace advocates at Moundridge High School were put on the defensive. "Everyone is talking about patriotism these days," wrote student Ellen Waltner, a member of Bill's winning debate squad, in the student section of the Moundridge Journal. Waltner reflected the ideals of her teacher: "We should show loyalty not only for our own country. . . . The time has come for world patriotism." But local people began to exhibit the spirit of vengeance that was sweeping the country. They organized a war rally at which people gave patriotic speeches and built a big bonfire to burn an effigy of Hirohito, the emperor of Japan. Selma Rich Platt, teacher of English and psychology, and an outspoken pacifist, refused to attend the pro-war rally. A few of her students began challenging her in class. One day in English class when the high school band was practicing the "Star Spangled Banner" across the street and the sound came through the window, some boys stood up at attention. Platt told them to sit down or to leave. They left and went downtown and reported the incident to some patriotic adults, who protested to Curt Siemens, the school superintendent. Someone put up a sign in the downtown drugstore window identifying Platt with Hirohito. Several times vandals disconnected wires in her car so she could not drive. The school board of directors called her in and asked why she had not applauded at a school assembly for a speaker who had given a patriotic recruitment speech. They warned that she would not be re-hired if she did not keep quiet about the war. One of the board members was Vernard Vogt, the newspaper editor. Platt thought that several of the board members of German ancestry had special reason to prove their patriotism. Although she was a widow with three young children, and had no prospects for alternative employment, Platt resigned at the end of that semester. Bill Juhnke came under the same kind of pressures. In one conversation with some patriotic students, Bill argued that conscientious objection to war was a respectable position. Even the highly respected former superintendent of the Moundridge schools, I.T. Dirks, had refused military service at Camp Funston in World War I. As in the case of Selma Platt, these students reported the conversation to leaders downtown. One businessman, Dave Roth, owner of the Ford agency, went to Curt Siemens to complain about Bill's statements and (according to at least one account) to suggest that he be fired. When Siemens told Bill about Roth's complaint, Bill immediately took things in hand. After school that day he went to the Ford agency and asked Roth, "Dave, do you have anything against me?" Roth was more subdued when confronted in person. He denied that he suggested that Bill be fired, but said that he should be careful what he said to students, because young people often hold their teachers in high regard. Bill then went to Jonas Goering, his father-in-law, who had recently bought a car from Roth. He asked Jonas to have a talk with Roth about the war and about his concerns regarding Bill Juhnke. The unspoken agenda, of course, had to do with whether Roth expected pacifist Mennonites to continue to buy Ford cars in Moundridge. (Roth, himself, was of Swiss Mennonite background.) Bill's vigorous self-defense in the face of patriotic criticism was a contrast to the Selma Platt's capitulation. Bill was a man, a popular teacher, and could call on the support of family and friends. Platt, although she was of Mennonite background and had relatives in Newton, was an outsider and isolated in Moundridge. Bill did resign his teaching position at the end of that 1941-42 school year, but he never said that his resignation was due to patriotic pressures in the community. The issue was clearly relevant, however, to his topic for a master's thesis–the teaching of controversial issues in Kansas high schools. He did not refer to the Moundridge case in his thesis. Before the United States entered the war, Bill was an energetic activist on issues relating to war and peace. He wrote many letters to public officials, organized peace meetings for Christian Endeavor and Hi-Y, and spoke out energetically for the Mennonite heritage of conscientious objection to war. It was important for Mennonites to be steadfast, especially at a time when, as he wrote to CE leaders in May 1939, that other "peace organizations are going militarist or losing their convictions." Harley Stucky, one of his high school students, years later spoke with great appreciation of Bill's forthrightness for peace in the face of looming war. Bill's predictions were not necessarily on target. In a letter of June 20, 1940, written at Kansas University in Lawrence, Bill wrote, "My guess is that we will not get into the war. Maybe I'll be wrong. I suspect it will be over before it would pay for us to join." In that same letter Bill said he had written to President Roosevelt, Senators Capper and Reed, and several others. In the July 30 issue of The Mennonite, the official Mennonite church publication, he recommended a peace proposal by Dr. Daniel A. Poling of Boston, and urged readers to write to their Congressmen. Bill's optimism and energetic activism were damaged when Congress passed the Selective Service Law (Aug. 1940) and declared war (Dec. 1941). Teaching at Buhler High School in 1943, Bill looked back and wrote, in a letter to a fellow Christian Endeavor leader, that the adoption of military conscription "sort of broke my enthusiasm for democratic government. I am absolutely sure that most people didn't want conscription . . . ." He was disillusioned with President Roosevelt, and did not see anyone on the national political scene that he could wholeheartedly support. When America mobilized for total war, pacifists were marginalized and largely silenced. Bill's summer studies at Kansas University in Lawrence offered opportunities for him to talk with other people about issues of war and conscription. He reported about an extended conversation with Mr. Cameron, the head of the draft board in Lawrence. Bill needed to have his conscientious objector papers notarized, but Cameron refused to do so. Cameron advised Bill that a III-A "dependency deferred" classification would keep him out of military service without having to sign up as a conscientious objector. Cameron then "told me a long story about Kenneth Weaver who resigned from Lawrence High School." Weaver was a McPherson College graduate, a conscientious objector who was pressured out of his job at Lawrence. Weaver's fate was presumably supposed to be a warning about what happens to conscientious objectors in wartime. Bill wrote to Weaver in Washington, D.C., where he had taken a job with the "Civic Education Service" that published Civic Leader and Weekly News Review. Another person in Lawrence who tried to argue Bill out of his pacifism was Prof. Ernest E. Bayles, professor of education. Bayles was a pragmatist who invoked Einstein's theory of relativity to argue that truth was relative, and that relativism in philosophy implied democracy in politics. One can arrive at "reasonable right" with the scientific method, taught Bayles, but "absolutism" (an error he said was associated with Aristotle and promoted by the Classicists such as Hutchins and the University of Chicago) is highhanded and dictatorial. Relativism is democratic; absolutism is dictatorial. Bill apparently found Bayles' case for liberal thought and liberal democracy quite attractive. He also was impressed that Bayles had defended Kenneth Weaver and his right to keep his teaching job at Lawrence High School. But Bill struggled with Bayles' definitions that categorized pacifism as anti-liberal and absolutist. As Bill put it in a letter to Edwin Stucky, in CPS camp: "Relativism is liberalism in thought; pacifism is absolutism because the pacifist opposes all war and the religious pacifist says his belief is founded on the authority of the Bible or of Christ." Bill saw this as a problem, and did not know how to resolve it: "Do I as a pacifist believe in Dictatorship? ‘No!' Do I as a pacifist believe in Democracy? ‘Yes!' Does the mainspring of my belief in pacifism come from any one single authority? An authority infallible? Perfect? Final? Ultimately true? There is a question for a thoughtful pacifist." Part of the resolution, as Bill saw it, was "that you can hardly separate the social from the religious. Jesus was the great humanitarian, going so far as to offer his life for his cause." Bayles surely forced Bill to think some new thoughts, but not to abandon his commitment to Christ. Bill greatly enjoyed discussing ethics and theology in personal conversations, Sunday School classes, and correspondence with friends. He did not attempt to share his theological thoughts in church publications, perhaps because he had not arrived at a coherent synthesis and perhaps because he sensed that he was on a liberal fringe. He liked to apply what he called "a left wing intellectual approach," but he feared that liberals in Mennonite circles would be misunderstood and misinterpreted. A liberal, Bill wrote in one letter, would be "stamped ‘cock-eyed' by some; he will be accused of ‘losing his mind' by others (But the enemies of Christ accused him of this too.)" Bill wanted to identify with Christ's persecution but also to find acceptance in his own social circles. A Christian liberal might find, he hoped, "a few who will appreciate him in his own time and give him intellectual fellowship and social approval." In fact, Bill did find that acceptance in his home congregation and in the Mennonite denomination. The Selective Service System made room for religious conscientious objectors to work in Civilian Public Service Camps in projects deemed to be of national importance. The government organized the labor projects, and the Mennonite, Church of the Brethren, and Quaker churches organized the camps and paid a minimal allowance to the drafted men. The churches needed experienced leaders for the CPS camps. While he was teaching at Buhler, he was invited to volunteer for CPS leadership, but he declined. Such a change would have probably involved at least some time of separation from his growing family. A second child, Janet Ann, was born November 26, 1942. A CPS position, even if it were directorship of one of the camps, would have involved a financial sacrifice. There were other young married men with children who did accept CPS camp directorships, and who took their families along with them. If Bill had accepted that invitation, he would have experienced a different environment and new challenges. It would have expanded his world in many ways. Bill carried on some correspondence with friends and former students who had been drafted and were in CPS camps. His younger brother Walt was his most important correspondent. Walt was a radical pacifist who came to believe that his decision to work in the CPS system was a compromise with an evil war-making order. If his CPS work was really of "national importance," its effect was to release someone else to go and fight. In September 1944, Walt wrote to Bill that he had set a date in October when he would walk out of camp, unless he was convinced otherwise. Walt knew Carl Stucky, a member of the Hopefield Mennonite Church, who had taken the absolutist position and had been put in prison. Walt said his greatest concern was how such an action would affect his parents and younger sisters, Marie and Martha. Bill encouraged Walt to stay in CPS. The program might involve compromise, but no one could be entirely morally pure. Bill quoted some writings by Guy F. Hershberger, a teacher at Goshen College who supported the CPS option. Walt finally decided to stay in CPS. He said that his older brother Bill was kind of a father-figure for him, as he was not able to discuss such matters with their father, Ernest. As a peace activist in the pre-war period, Bill Juhnke was an enthusiastic participant in the American political process. He had been Americanized in ways far beyond those of his German-speaking parents. He freely used the personal pronoun in speaking and writing of United States foreign policies as "our policies." In correspondence he quoted John Dewey, progressive philosopher. He shared Dewey's belief that public school teaching was an opportunity to promote higher ideals of democratic civilization. Then the war forced Bill into a more defensive and withdrawn position. He lamented the isolation of the wider peace movement. He feared that his outspoken activism had gotten the attention of the government, and that the Juhnke home in Buhler had been bugged by the FBI. As the war dragged on, he worried that he might be drafted after all. In the summer of 1943 Paul McNutt, the War Manpower Commission chief, told the Selective Service System to reclassify all those deferred because of dependency. In December of that year, Congress passed Wheeler bill (Public Law 197) that mandated partial protection for fathers. Even so, Bill feared that manpower shortages might lead to his being drafted. So in the spring of 1944, after two years at Buhler high school, Bill left teaching and began full time farming. As a farmer he hoped to claim an occupational deferment. The move home to the farm near Elyria was a defensive inward shift. Three years earlier he had imagined that a master's degree would open up new opportunities, perhaps in high school administration: "No stone will be unturned, in looking for a better job." Now he was back on the farm, soon to be teaching in a rural one-room primary school. Bill remained a liberal Christian pacifist throughout his life, but never with the same optimism and energy as in those years before the war, 1936 to 1941, when he was a crusading young pacifist high school teacher. |